A flagship project for changing times

14. February 2024

2. December 2022

Russia’s attack on Ukraine challenges Europe and the world. For Germany, the EU and NATO, the invasion represents a profound turning point – and with it, serious changes in security policy.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 will surely figure prominently in the history books. For the Russian invasion was not merely a flagrant violation of international law; it has also triggered a far-reaching process of change in Europe, whose political, economic, and military consequences it is too early to evaluate in full.

NATO General Secretary Jens Stoltenberg was not exaggerating when, deeply worried, he stated that the war in Ukraine had sparked the “biggest security crisis in Europe since the Second World War”.

To be sure, however, the war in Ukraine is not the sole cause of these geopolitical transformations. On the contrary, a whole host of very different and partly diverging developments are influencing Europe’s future and will continue to do so. Here is a brief overview.

USA AND NATO

In coming years, close transatlantic ties to the United States and membership in NATO will continue to be Europe’s – and especially Germany’s – basic life insurance policy. Yet Europe is no longer a top US foreign and defence policy priority. The fast-growing nations of the Pacific Rim and their strategic military significance in the Indo-Pacific region have for years played an increasingly important role in Washington’s geopolitical and economic calculations. The creation in 2021 of the trilateral AUKUS alliance between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States is just one example of this trend.

RUSSIA

Owing to its offensive war against Ukraine, the regime in Moscow is no longer viewed in the West as a valued strategic partner, but instead is now vilified as its greatest threat. The previous credo of German governments that security could only be achieved in concert with Russia rather than by opposing it, has proved to be political miscalculation. As Chancellor Olaf Scholz stated in a government declaration on 22 June: “For the foreseeable future, a partnership with Russia of the kind still envisaged in 2010 as a strategic concept is inconceivable with Putin’s aggressive, imperialist Russia.” In plain language, this means that Germany must now rethink and recalibrate its previous Russia policy.

CHINA

The People’s Republic of China has long since ceased to be a “sleeping giant”, but instead seems to be pursuing its political goals with a clear strategy. Only gradually has the realization dawned on the West that China, while not posing a direct military threat due to geographical distance, has become a systematic competitor, engaging as discretely as possible in a consistent policy of expansion. China is therefore America’s top foreign and defence policy priority. President Joe Biden has gone so far as to speak of a global struggle between the democracies and the autocracies. And indeed, China’s ambitious “Silk Road” project, though ostensibly motivated by economic and technological considerations, is driven even more by ideology and power politics.

TAIWAN

The conflict over Taiwan is a textbook example of just how strongly ideology, power dynamics and history dominate China’s foreign and defence policy. China’s position is clear: Taiwan is and remains a province that historically belongs to the People’s Republic. Equally clear is America’s policy of strategic ambiguity, which consciously leaves open the question of how the United States would react to a Chinese attack on Taiwan. If the conflict now being stirred up by China through military threats and attempts at intimidation were to escalate into a war because of an offensive military manoeuvre, this would not only have a massive negative impact on the security of the nations of the Indo-Pacific region. It would also lead to massive disruption of global supply chains, especially since Taiwan’s IT industry produces basic systems and components for Europe’s high-tech industry.

EUROPE

The EU and NATO play a complementary and mutually reinforcing role in maintaining peace, security, and stability. But in order to overcome Europe’s longstanding historic dependence on the US and to assert its own (security) interests vis-à-vis the US, Europe must do more for its own strategic sovereignty and thus for its own defence. This is even more valid given that future political developments in American harbour uncertainties and risks for the continuity of US foreign and defence policy.

Germany’s former foreign minister, Sigmar Gabriel, repeatedly pointed out that Europe should do more for its own defence, because in a world of meat-eaters, vegetarians would have a hard time surviving. And it was none other than Jean-Claude Juncker, the long-serving President of the European Commission, who made it plain that Europe finally had to develop a “global policy capability” and, owing to its immense economic and technological potential, to enter the world stage as a stronger political actor. The efforts by many European nations to meet the NATO goal agreed in 2014 of spending two percent of gross national product (GDP) on defence reflect this development.

Sweden and Finland joining NATO

Prompted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and concerns for their national security, these two Sweden and Finland applied to join NATO in summer 2022. Sweden, a byword for political neutrality for over 200 years, and Finland, which shares a roughly 1,300 km-long border with Russia, will – presuming the accession protocol is ratified by every NATO state – increase the number of NATO member nations from 30 to 32, as well as substantially strengthening the Atlantic alliance’s northern flank.

EUROPE (ALMOST) WITHOUT BORDERS (Interactive)

Ukraine and Moldova to join the EU

The European Union unanimously acknowledged Ukraine and Moldova’s status as candidate countries with 27 ‘yes’ votes on 23 June 2022. Once all the criteria are met, the accession of the two countries into the EU community of nations would bind them more closely to Europe. Thus, in a few years’ time, the EU could have 29 members, up from its current 27.

New alliances with Russia

The planned expansion of NATO and the EU are naturally a thorn in the side of the political leadership in Moscow. It is there no coincidence that President Vladimir Putin’s first trip abroad since the invasion of Ukraine was to Central Asia in June 2022. He described five states (Kazakhstan, Kirgizstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) as “historically Russian”. Furthermore, at a summit meeting of nations bordering the Caspian Sea (Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Russia), Putin evidently weighed the possibility of new alliances. Still difficult to assess are Russia’s attempts for a rapprochement with China, which has been notably reserved in its criticism of the Russian attack on Ukraine.

Russian rocket systems in Belarus

In a visit to St. Petersburg in June, Putin announced that Russia would be stationing Iskander-M missile systems in Belarus in coming months. These mobile launchers can fire short-range systems as well as cruise missiles, tipped with conventional or nuclear warheads. If the systems are stationed as planned, it would pose a new threat to Europe, especially to the frontline NATO nations Poland, Lithuania and Lativia, all of which share a border with Belarus.

Something new – national security strategy

In his “Zeitenwende” (turning point) speech on 27 February, Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced a special €100 billion fund and an initiative to whip the Bundeswehr back into shape as Germany’s immediate responses to Russia’s unjustified offensive war against Ukraine.

In addition, under the auspices of the German Foreign Ministry, a security policy white paper is currently being drawn up with the aim of defining a national security strategy for Germany. This is something new. Germany has never had a national security strategy before.

The profound geopolitical changes that have taken place in recent decades, e.g., the reunification of Germany, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the senseless war in Ukraine, make this strategy a crucial necessity. Forming the basis for this is, among other things, a clear expansion of the meaning of “security”. This is no longer confined to external, i.e., military security, but now extends to internal and socio-economic security, as well as cyber, energy, food, raw material and supply chain security.

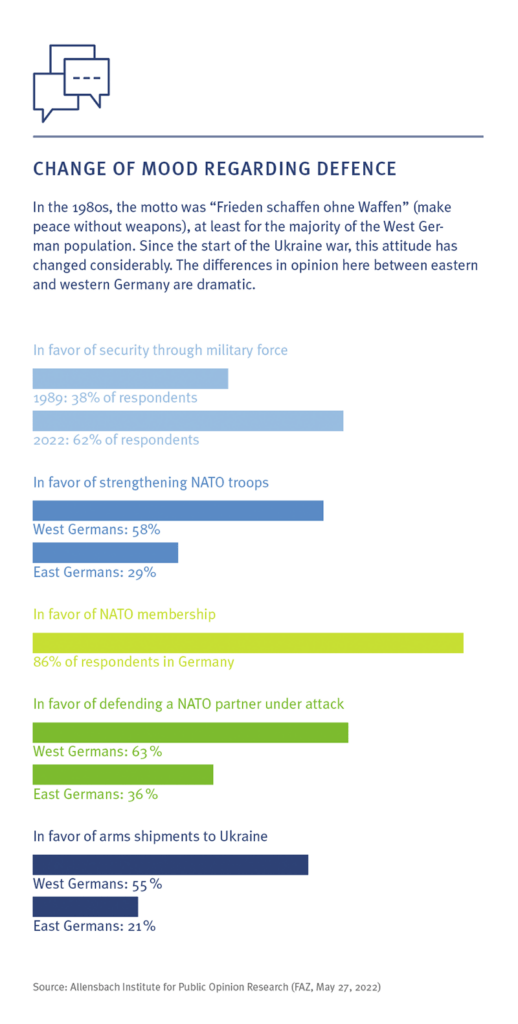

It comes as no surprise, then, that this multifaceted development is also affecting public opinion. A significant change in German attitudes concerning the sensitive issues of defence and security policy is apparently underway. For instance, the majority now strongly approves of achieving security through military strength as well as Germany’s continued membership of NATO and the controversial supply of weapons to Ukraine.

Whipping the Bundeswehr back into shape

The special fund for the Bundeswehr announced by the German government, coupled with a substantial increase in the investment portion of the defence budget, will make it possible to reequip the German armed forces, enabling them to carry out their core mission of defending Germany and its NATO partners again. By 2025, every active soldier is to be kitted out with completely new battle dress uniforms and protective gear – this, at least, is the current Bundeswehr plan. The resources are also intended to turn the Bundeswehr into a European force multiplier in NATO and the EU. The special fund will be used to bridge capability gaps resulting from years of spending cuts.

The economic plan associated with the special fund offers a good overview of the planned expenditure, which is divided into four dimensions:

The Air Dimension: The largest share of investment (€33.4 billion) is earmarked for the “Air Dimension”, with the Air Force, Army, and Navy all benefitting. The procurement programmes include, among other things, 35 American-made F-35 multirole combat aircraft, 15 Eurofighter Electronic Combat Role (ECR) jets, and sixty Chinook CH-47F heavy transport helicopters.

The Command & Control / Digitization Dimension: The second largest share of investment (€20.7 billion) is intended to improve Germany’s command and control capabilities and push ahead with digitization. In particular, the procurement of advanced radio technology will enable German troops to communicate with their NATO comrades via encrypted wireless links.

The Land Dimension: Around €16.6 billion has been set aside for the “Land Dimension”. Planned investments include, among other things, retrofitted Puma infantry fighting vehicles and successors for the Marder and Fuchs/Fox systems. Part of the resources will go on the development of a new German-French main battle tank, the Main Ground Combat System, or MGCS.

The Naval Dimension: This dimension is due to receive €8.8 billion, encompassing, for example, the K130 corvette, the F-126 frigate and the 212 CD submarine, which is currently under development.

Securing Germany’s long-term future

At present, it is still not clear if Ukraine will be able to withstand Russia’s military preponderance over the long haul. It would be desirable and sensible if diplomatic channels were to remain open, enabling the difficult work of trying to find a viable political solution to end the war in Ukraine through diplomacy and dialogue to continue.

Moreover, the changes in the megatrends outlined here show that policymakers need to rely more strongly on credible military force again. Security isn’t something that can be taken for granted, nor can it be achieved without striving to achieve an independent defence capability.

For these reasons, the planned defence expenditure should be understood as a strategic investment in security, thus making a material contribution to securing Germany’s future. This is absolutely vital. For the radical transformation of Europe’s security architecture is already well underway.

Click here to receive push notifications. By giving your consent, you will receive constantly information about new articles on the Dimensions website. This notification service can be canceled at any time in the browser settings or settings of your mobile device. Your consent also expressly extends to the transfer of data to third countries. Further information can be found in our data protection information under section 5.